Propaganda is arguably the most useful political tool a government can possibly use, especially in times of war. The power of propaganda was debatably most successful in World War II in Nazi Germany, as the government was able to keep its citizens in the dark on the severity of its own crimes and also keep them convinced the Germany was winning the war, up until the very end when the Allies began occupation. Nevertheless, propaganda was a useful tool on both sides. It raised morale, both for soldiers and especially the home front. It also convinced its audience that it was doing the right thing: for Americans, World War II was about the triumph of good over evil. Wartime propaganda reflected this sentiment greatly, and it is seen in newspaper cartoons, animated cartoons, ads, film – any popular media that could be penetrated by wartime propaganda, was.

Newspaper and Magazine Cartoons

Newspapers were the primary source of information during World War II. They were also home to political cartoons and ads. Cartoons targeting the Japanese projected similar themes; they usually portrayed the Japanese with circular-rimmed glasses, big teeth, and big ears or occasionally as monkeys or rats, played up the effect of Japanese-accented English, and gave an overarching message that the actions of American civilians directly affected the results of soldiers overseas. These cartoons succeeded in stimulating in American civilians fear and hatred for the Japanese far beyond what they could understand from their military counterparts. This mindset would saturate American public opinion so deeply that it would alienate the Japanese and Japanese-Americans from the general population. Below are a few examples of the endless political cartoons targeted at the Japanese.

In the following cartoon, a louse serves as a metaphor for the Japanese, degrading them to insects while still providing the stereotypical physical features like slanted eyes and big teeth. The most important part of this cartoon is the last sentence, suggesting these “lice” should be “completely annihilated.” The irony of this cartoon, obviously, is that two Japanese cities would indeed go on to be “annihilated” in August 1945.

Here are some cartoons portraying the Japanese as monkeys or rats. Cartoons such as these reduced the Japanese to the status of animals; these cartoons told Americans that the Japanese were savage beasts that needed to be defeated.

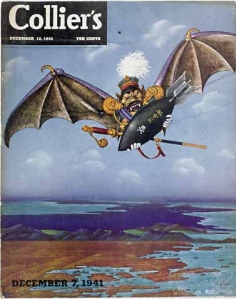

This last one also reflects popular culture of the time; the Japanese soldier on the front of the magazine is depicted as a flying monkey, a type of monster in the classic movie The Wizard of Oz, which debuted about three years prior to the release of this magazine. Using a well-known film helped create a bond between Americans: a familiar film connected to a familiar enemy.

As mentioned before, propaganda utilized whatever chance it could at encouraging citizens to engage in the war effort, whether it be by “staying quiet,” buying war bonds, or so forth. This is particularly noticeable in the above cartoon on the top right, the one that says “Don’t talk… rats have big ears.”

A powerful and popular tactic during wartime, these cartoons also exploited the image of the innocent and victimized woman to make the enemy even more monstrous than what they could do through humor. In the following cartoons, women are portrayed as the helpless “damsels of distress” at the hands of Japanese soldiers. The innocent women taken advantage of by Japanese men is arguably worse in a moral sense than soldier-on-soldier violence, because the innocent woman at home should have been protected by her man who is away at war. Using this as a tool added more emotion and moral justification for the war and for hating the Japanese.

All of this is not to say that Japanese did not provide fuel for the fire created by these cartoons and ads. The Bataan Death March was tragic and brutal, and media did not pass up the opportunity to spin the event into propaganda. In the following cartoon, the eye is immediately drawn to a sketch that alludes to a well-circulated picture from the Bataan Death March– that of an American GI being abused by a Japanese soldier. This image is so powerful because it became universal to its audience; that American GI could be any Johnny or Bobby whose mother was at home weeding her Victory Garden.

Arguably the most powerfully ironic cartoons are the two following ones; they call for giving the Japanese “a dose of [their] own medicine,” implying attacking the Japanese with bombs in return for Pearl Harbor. In both, an arm representing the Allies (and Uncle Sam in the one on the right) shoves bombs down a Japanese man’s throat. Of course, this was the end result of the Pacific War: America did deliver “a dose of [their] own medicine” in the form of atomic bombs. These cartoons reflected the general desire to inflict as much damage on the Japanese as possible, in the names of vengeance and victory.

Film Cartoons

While Saturday morning cartoons are now just a memory, television cartoons from great animating companies such as Disney and Warner Brothers dominated child entertainment. Love for these cartoons was not limited to children; their influence reached the hearts of adults and people around the world. However, many people today do not realize that some label Walt Disney as a “war profiteer.” He eagerly became involved with the war effort, mostly making instructional films and, of course, cartoons. The following clip, titled “Commando Duck: Donald Duck Against the Japanese,” a cartoon using the beloved character Donald Duck as an American soldier fighting against the Japanese overseas.

(If you’re having trouble watching this video, click here.)

While the video is mostly fun and games about Donald Duck in true Disney fashion, the cartoon is subtle but sure in its depiction of the Japanese. Starting around the 2:00 minute mark, two Japanese soldiers accidentally hurt each other while in camouflage, apologize, and bow to each other back and forth for an unnecessary amount of time- a jab at the unfamiliar culture associated with the Japanese. Around the 2:25 minute mark, one Japanese soldier is aiming his gun and says in heavily accented English, “Time to shoot the Nazis I hope.” This is another taunt at the Japanese, in order to portray deficient intelligence; obviously the Japanese were aligned with the Germans and there were no Nazis fighting in Japan, so this soldier’s remark is not only incorrect but also represented as stupid. At the 2:30 mark, this same Japanese soldier accidentally points his gun in the direction of one of his comrades. To this, the second soldier says (again in heavily accented English), “Japanese custom says, always shooting a man in the back, please.” In a war of morale and of good guys pitted against the bad, the man who shoots another in the back is symbolically wrong. To shoot another man in the back was unjust, unfair, and even cowardly; this cartoon paints the Japanese thus so.

Warner Brother also created cartoons for propaganda purposes. The following, “Tokio Jokio,” was ultimately banned from television. It takes the same basis as the Disney cartoon, but pushes elements of racism and opinions of Japanese much, much farther. It is easy to see why it was banned, because it is definitely offensive outside of a wartime mentality. The cartoon speaks for itself, leaving no need for individual interpretation.

(If you’re having trouble watching this video, click here.)

The Japanese are depicted with the popular characteristics of Japanese at the time: big ears, circular-rimmed glasses, big teeth, and ending almost every sentence with “please.” Rather than examining the relationship between American and Japanese soldiers, this cartoon serves as a sort of “roast,” making fun of Japanese unpreparedness and sloppiness.

Another adored character in American animated features, Bugs Bunny, was utilized to paint the Japanese in a bad light as America’s favorite rabbit serving some time in Japan in this clip released in 1944. “Bugs Bunny Nips the Nips” touches on many stereotypes of Japanese culture, including sumo wrestlers, geishas, and the consistent physical depiction of Japanese soldiers seen in the other cartoons.

(If you’re having trouble watching this video, click here.)

In many ways, this cartoon is the most reflective of American attitudes out of the three presented here. Sweeping generalizations are made of the Japanese, along with references to military culture. For example, Bugs Bunny is constantly painting Japanese flags throughout the cartoon; drawing flags was often a sign that a kill was made (i.e., if you shot down a Japanese plane, you painted a Japanese flag on your own plane). This cartoon also sheds light on racial slurs, shown at the 5:50 minute mark. As Bugs Bunny hands out bombs made to look like ice cream, he says, “Here you go, monkey face,” and “One for you, slant eyes.”

Cartoons were an easy way to reach the American general population as they were deeply implanted into entertainment culture. As jokes, they provided laughter and perhaps even comic relief from the horrors of war depicted on the news and on the radio. However, the laughter left a mark on memory. A child could laugh at Bugs Bunny calling a Japanese soldier “monkey face,” but it also normalizes the action and makes it okay. These cartoons justified racist behavior and hatred for the Japanese.

Resources:

http://ronanshonorsushistoryii.mrsronansclasses.com/Mrs._Ronans_Honors_U.S._History_II/Anti_Japanese_WW_II_Propaganda_Posters.html

http://chumpfish3.blogspot.com/2006_03_01_archive.html

Wikipedia

13 thoughts on “Wartime Propaganda: Good vs. Evil”